Or risk getting lost in an ever-expanding web of multiverses from which there is no escape.

By Jon Pampell, Mastermind GM, Pathologically Overprepared Dungeon Master

If you’re a game master, forever or otherwise, you’ve encountered it; The discomfort. The creeping chill. That odd, bloating sensation spreading throughout your party’s story. It’s Narrative Creep, and it’s especially infuriating to DMs that write their own material.

Does this sound familiar?

THIS IS FINE.

You create this scenario with complicated, colorful characters in a complicated, colorful setting, and you can’t wait for your players to interact with it all. Colorfully. Complicated…ly.

But then the more you think about it, the more you realize that these characters have to have their motivation rooted in a real world or they feel hollow. You furiously scribble the character’s motivations into your notes.

People are largely a product of their environment, so why is the setting the way it is?

Do your players need to know these things to be able to live in this world? Can the characters change the world? How exactly can they do that? Oh God, if they change the world what will it look like then? What branches of the multiverse do you need to write? This could take months!

Congratulations! You’ve got Narrative Creep: the involuntary expansion of your storyline from a tight, well presented tale of good triumphing over evil to a meandering, chunky slog through an empty world you wish you’d never conceived.

I’ve struggled with Narrative Creep like you would not believe. My long-suffering group of friends know that my game-mastering style tends to run long, because I give my players maximum freedom to do as they wish with the world I set up for them. I invite them to come play on my playground, so to speak.

Now, if you’re a GM reading this, the alarm klaxons might be starting to blare in your head. Player freedom comes with a ton of pitfalls, at the bottom of which are impaling spikes or buzzsaws or flesh eating whatsits. Such freedom is dangerous to your sanity as a GM, and you are right to fear it. However, with the right lore, written beforehand, it can be one of the most rewarding ways to play tabletop games. To pull it off, your narrative clues need to come up organically during play, and they need to be effective enough that you don’t have to account for a hundred different parallel universes to be properly prepared.

In come the hooks, little things I drop into the story to get players moving in the right direction: Toward the parts of the story I’ve written out beforehand. To make these narrative clues appear to be logical expressions of the world, they have to have a certain internal consistency: Grounding, if you will.

The problem is that significant events don’t often come with full explanations right out of the box. Crashed satellites rarely just come out and tell us why they lost contact with ground control. The number of signed confessions stapled to dead bodies is vanishingly small. Shocking, I know. There are people whose literal jobs are to fashion themselves into experts on these subjects, so they can tell the world exactly what happened. There are investigations led by detectives and forensic specialists. There are panels of experts with white lab coats and expensive degrees. Discerning the truth from the facts is an arduous process, and the further we deviate from this hard reality, the less legitimate the players’ triumph feels as they make their world shaking, life and death decisions.

So how do we strike the balance between immersion and fun? We cheat.

In D&D we take shortcuts. There’s history checks, religion checks, magic rituals, speaking with the dead… All examples of things that extraordinary people like our adventurers can do to cut through the tedium of measuring blast craters or reading ancient tomes. So, since we are already diverging from reality, how do I give that feeling of discovery to my players without writing triple the amount of content before every session? I can’t just have the Exposition Express pull into the station and unload that sweet, sweet lore directly into my player’s faces, so they make the correct call on what to explore next.

So, I sprinkle my breadcrumbs: A bookmarked page here, a hastily scrawled note there. Scuff marks on the wooden floor. Fire damage in the bedroom. A babbling patient in the asylum. Divorce records. Tormenting visions. Flash bulb residue. It may seem like a lot now, but if I can reliably direct my players, I have a shot at only having to prepare a small, dense area of the world as opposed to an entire continent of empty-feeling side quests. My players get where they need to go while still retaining their agency. They feel in control of the narrative, and it makes for a wonderful experience for everyone.

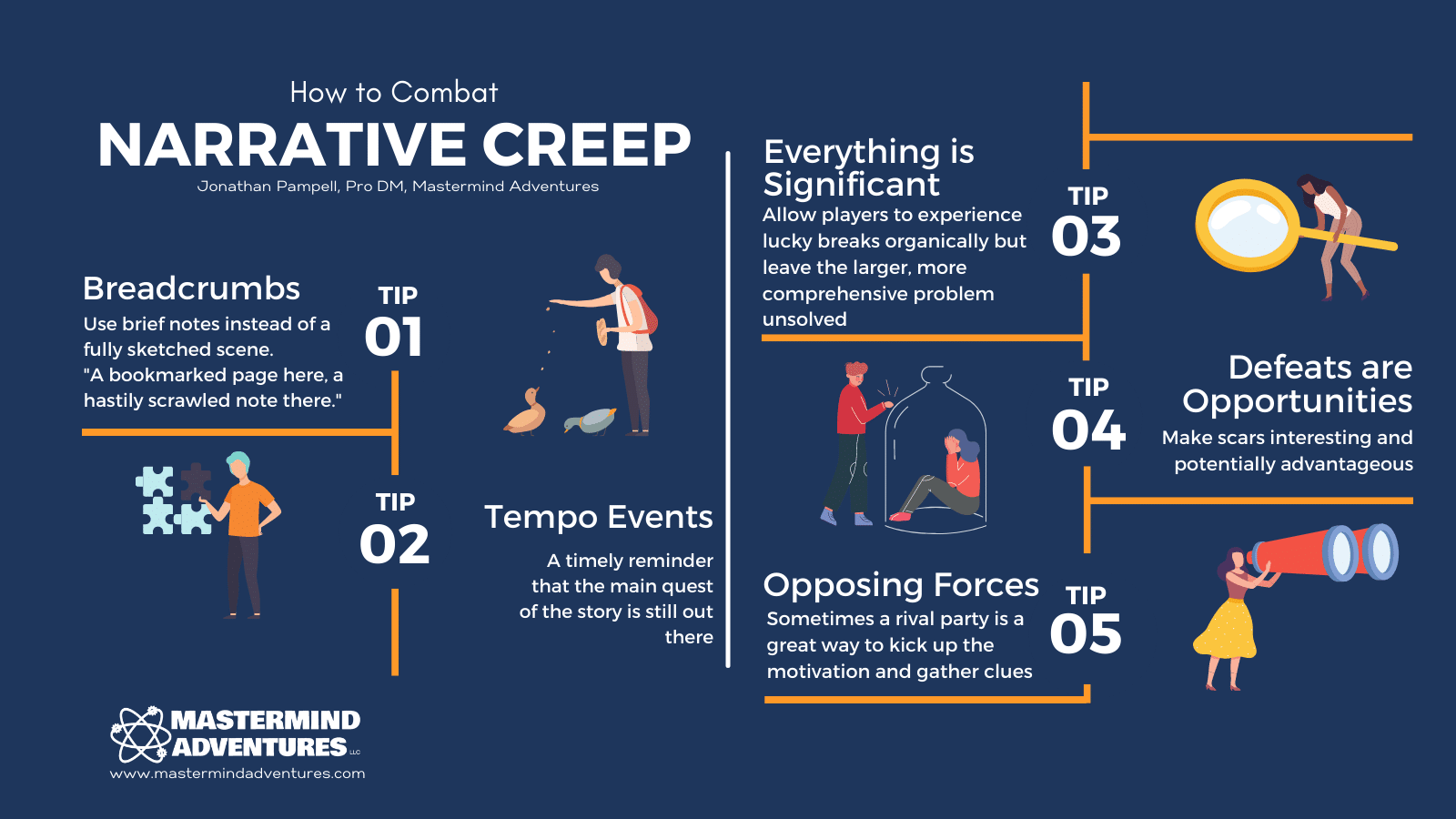

I’ve learned to use a few general strategies on how to combat Narrative Creep without sacrificing player agency. These do require a bit more preparation and effort in the short term, but they’ll motivate your players to get to the good bits of your setting without being so obtrusive that the players feel like their agency is being violated. The following may just help your story stay on track for the long term, and, in turn, help you focus your creativity and energy on the right part of the story between sessions, cutting your total prep time down to a surprising degree.

Tempo Events

This might be the most straightforward method of keeping the narrative focused. Tempo events are a timely reminder that the main quest of the story is still out there, and it affects the players and those around them. Maybe the villain of the story comes and burns a character’s house down, or there’s a scream down the hall of the spooky mansion. Maybe a portal to hell opens up at the King’s coronation.

Wizards of the Coast uses tempo events in their modules; notably, Wild Beyond the Witchlight has a whole mechanic about it, keeping things moving with a super slick time indicator on the campaign map.

Tempo events don’t have to be a flashing neon sign with the letters “P-L-O-T” but they should serve as reminders that significant things are happening in the world at large that don’t necessarily require the party to be present.

The downside here is that tempo events are the most jarring form of narrative focus. It’s the GM’s way of slapping the players and telling them the story is right there, and it needs to move on. Too many of these and you enter the realm of the Railroader GM.

If you are a Railroader GM, I love you and respect you, but that’s not what this post is about. You keep on doing your tightly controlled story that happens exactly as you envision, and I’ll stay over here pretending I’m not jealous of your focus and commitment to your story.

Everything is Significant

I like to keep a few of my breadcrumbs unattached to sprinkle around when my players need some direction. Call them lucky breaks, hunches, coincidences. Whatever you call them, they can happen any time, and they still give the players the feeling of discovery and triumph when they put the pieces together. The trick is to allow the players to experience the lucky breaks organically but leave the larger, more comprehensive problem unsolved.

Let’s say the party wants to talk to a pickpocket they’ve caught in the act. He’s stolen several coin purses today. All of the purses have the exact same amount of coin inside of them. Ask a merchant forcefully enough, and he tells you that happens to be the exact amount needed to bribe a guard and signal that you are protected by the organized crime family in the city. This clue could just as readily be found on a dead guard, or dropped in the street, or given under a table when the party starts asking questions.

Another example might be a bird’s nest with flash paper woven into it. There’s writing, but it’s hard to make out. Two words jump out, though: killers, alkahest. This tells the party a few things: This bird pilfers someone’s notes for nesting. Flash paper is meant for burning and secret keeping. Alkahest is an alchemical substance. Is it hard to get? What kind of person would know about this?

These floating breadcrumbs can sometimes turn an overwhelming open world into a slightly less mysterious one.

Defeats are Opportunities

When the party runs up against the brick wall of defeat, whether it be in combat or during an investigation, make sure the events change the scenario in some way. Defeat doesn’t necessarily mean death. Our scars remind us of who we are and what we’ve done: Make these scars interesting and potentially advantageous.

If one of the players or an adopted NPC is severely injured, the local healer may have something to say about the goings on in the area. She belongs to no church, but she represents a particularly hands-on genius loci. Her guardian spirit might even bless the character if they took the wound in the process of doing good in the community. Here, a short-term setback becomes a boon.

Imagine that a target the party was tailing got away. Perhaps a thieftaker mistakes the party for his prey and, after a brief altercation, asks some pointed questions: Questions that give the party some clues about where to look next. “Hey, you guys are horning in on my case. Back off or there will be trouble!” Boom. Now the party has an unwilling guide or a foil to be exploited later.

Let’s say a dastardly henchman jumps one of the players in a dark alley, and perhaps the player character notices a strong smell just before their lights go out. Then they notice the smell again when talking to a significant NPC. Ah yes, a lead!

And let’s not forget that tried and true “oh no, the villains have kidnapped us instead of killing us in the street” method. It’s cliché and overused, but it’s used so frequently for a reason. Not every villain is a mastermind, and their henchmen probably scored even lower on their fantasy SATs. Mistakes are made, heroes are tied to chairs, hapless henchmen spill the beans on the villain’s dark plans.

Opposing Forces

Sometimes a rival party is a great way to kick up the motivation and gather clues your players have not found yet. Rival parties need their own motivations, but they will be a font of information and a good source of tempo events that feel natural if the party gets lost. Don’t make your opposing forces entirely hostile. Just make them parallel in their interests and goals.

I’m particularly fond of making the rivals a bizzaro version of the party. For example, if the players have chosen to use charisma casters like sorcerers and warlocks, their foil can be a wizard that lords his intellect over pretenders that were simply handed their power. If the player party has altruistic motives, have the rival party be purely mercenary. Have the opposing force rub salt in the player’s wounds once in a while. Give your players a reason to resent these people.

When things are looking particularly dire for your players, send in the cavalry your players least want to see. “Ah, I see your ineptitude has you in a bind again. Can’t say I’m surprised,” says the smug jerk of a bard. “We’ll take it from here.” Later in the story, the roles can be reversed, and the players get to see these blaggards get a taste of karma. In the meantime, players can look at what the other party is doing and exploit that knowledge for their own benefit.

Tastier Bread Crumbs

This one is a judgement call on your part, GM. If your players aren’t picking up on your living, breathing world full of breadcrumbs, they may just not be interested in the kind of story you’re trying to tell or the way you are telling it. Maybe they want a break from the real world and its complicated narrative, so they are more interested in the game aspect of things. Notably, loot.

I know what you’re thinking. Don’t feed the bear, or he’ll start coming around at 2 a.m., knock over your trash cans, and creepily watch you while you sleep (yes, this has actually happened to me). This method also has some drawbacks. However, not every magic item or bauble makes balancing encounters harder.

Let’s say your players are investigating a strange set of happenings in the city. You’ve hinted that the economy is in an upheaval here thanks to new advances in medicine. You want them to realize that a huge corporation has pushed all the independent alchemists out of the city with political pressure and scare tactics, but they just aren’t keen on asking questions. Time for an encounter! The barbarian has a strange substance spilled on his hand, reducing the limb to blackened bones. What’s this? He can still move it? His hit dice are gone? Oh he’s casting vampiric vouch on instinct now? Oh no, it’s spreading! Better go see an alchemical specialist to get some answers. Get those players into that alchemist’s shop, and get those lips flapping about said alchemist’s woes.

Obviously, this is not an exhaustive list of practices that will get you out of all of your narrative jams, but it’s worked for me. It’s allowed me to focus my creative energy onto areas of my campaigns with an intensity I thought impossible before. The methods are less about shrinking the world where your story takes place and more about influencing player choices so you can make your story denser and more alive.

In the end, only you know your players and their characters, and those players are there for your games. Whatever you’re doing must be working. Keep going. Just remember that this is a game for you to play too, GM. Using one or all of these methods now can save you a lot of prep work later. Play with your narratives until they suit you, and don’t let Narrative Creep turn your prep area into a tangled mess of red yarn and coded notecards.

Unless that’s your thing.

Jonathan Pampell is a professional Game Master with Mastermind Adventures. When he is not writing the sixth branching timeline of one of his current games, he is working on a novel, shooting tiny paper targets, wrangling children, or playing video games. He is a father, a husband, a creative, and a combat veteran. As well as a silly voice enthusiast.

Leave A Comment